Someone told me recently that I was ‘normal’. He added that he didn’t mean I was an average person of average intelligence with an average life and average accomplishments. Actually, he thought of me as ‘a little weird, in a charming way’.

Someone told me recently that I was ‘normal’. He added that he didn’t mean I was an average person of average intelligence with an average life and average accomplishments. Actually, he thought of me as ‘a little weird, in a charming way’.  No, it was meant as a compliment, that I was sane and balanced in body and mind. I thanked him with a smile, ready to move to another subject. I don’t like being referred to as normal! It just sounds too boring… What he said next unsettled me: ‘I fear, Virginie, that normal people are in a minority these days. Everybody seems to have mental issues.’

No, it was meant as a compliment, that I was sane and balanced in body and mind. I thanked him with a smile, ready to move to another subject. I don’t like being referred to as normal! It just sounds too boring… What he said next unsettled me: ‘I fear, Virginie, that normal people are in a minority these days. Everybody seems to have mental issues.’

Was he right? Is normality really not the norm anymore? Is being normal abnormal? Anyway, what is ‘normal’?

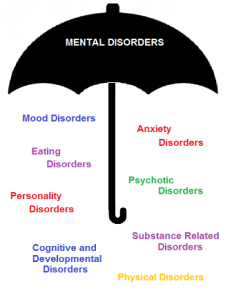

Every day we watch on television, computer and other screens people struggling with various degrees of personality disorders and mental illnesses. Of course, to grab the attention of the audience, the film and television industry targets dramas and blow them out of proportions. However, the issue is clearly not only on screens. If not directly you, I have little doubt that several persons in your life are affected, and as a consequence, it affects you too. There are more than 200 classified forms of mental disorders, more or less acute and dangerous (for the one afflicted and/or the rest of the society – I am putting terrorists in that lot of dangerously sick people), the like of bipolar disorder, narcissism, addictions, depression, self-loathing, paranoia, obsessive-compulsive, schizophrenia, anorexia, bulimia… Has it always been like this?

Every day we watch on television, computer and other screens people struggling with various degrees of personality disorders and mental illnesses. Of course, to grab the attention of the audience, the film and television industry targets dramas and blow them out of proportions. However, the issue is clearly not only on screens. If not directly you, I have little doubt that several persons in your life are affected, and as a consequence, it affects you too. There are more than 200 classified forms of mental disorders, more or less acute and dangerous (for the one afflicted and/or the rest of the society – I am putting terrorists in that lot of dangerously sick people), the like of bipolar disorder, narcissism, addictions, depression, self-loathing, paranoia, obsessive-compulsive, schizophrenia, anorexia, bulimia… Has it always been like this?

A part of me fears that the relatively recent development of individualism and introspection may have played an important role in the surge of mental disorders. Has our society fallen victim of constant self-analysis to the point of self-dissection? Another part of me thinks – hopes even – that human beings have always struggled with who they were, and the medical progress in brain researches have brought it to the surface, so that these struggles are now more understood and cared for.

A part of me fears that the relatively recent development of individualism and introspection may have played an important role in the surge of mental disorders. Has our society fallen victim of constant self-analysis to the point of self-dissection? Another part of me thinks – hopes even – that human beings have always struggled with who they were, and the medical progress in brain researches have brought it to the surface, so that these struggles are now more understood and cared for.

What I strongly believe, though, is that having a mental disorder or illness does not mean you are not ‘normal’. It just means you have a disorder or illness, and that’s it. Because, really, how do you measure ‘normality’? Take me: maybe I am mentally sane and balanced here in London and this day and age. I doubt my ‘slightly’ bohemian personality would have fitted into the standards of normality 100 years ago, or even in Asia today, and as a consequence, I could easily have fallen into depression (at least) in those circumstances . Also, normality is not only relative in time and space, it is also changing in one’s given life. I was not always in a good place mentally; I did battle my own demons, and it was serious. By the time my teenage years came to an end,

What I strongly believe, though, is that having a mental disorder or illness does not mean you are not ‘normal’. It just means you have a disorder or illness, and that’s it. Because, really, how do you measure ‘normality’? Take me: maybe I am mentally sane and balanced here in London and this day and age. I doubt my ‘slightly’ bohemian personality would have fitted into the standards of normality 100 years ago, or even in Asia today, and as a consequence, I could easily have fallen into depression (at least) in those circumstances . Also, normality is not only relative in time and space, it is also changing in one’s given life. I was not always in a good place mentally; I did battle my own demons, and it was serious. By the time my teenage years came to an end,  I had won, I had mastered these beasts. They left scars behind them that I can still feel. I don’t mind them, they are healed and help me remember how tough the fight inside me was and how easily the mind can go down a slippery slope. I hope that if one of these demons resurfaces one day, the experience and memory will help me nip its rise in the bud. One never knows if they are not lurking still.

I had won, I had mastered these beasts. They left scars behind them that I can still feel. I don’t mind them, they are healed and help me remember how tough the fight inside me was and how easily the mind can go down a slippery slope. I hope that if one of these demons resurfaces one day, the experience and memory will help me nip its rise in the bud. One never knows if they are not lurking still.

In fact, I am grateful that I was not always balanced. It enables me to understand and empathise better with people who are in a dark place, who are unstable, or who are struggling inside and need support. Could it be that the experience made me more human? If so, could it mean that being always ‘normal’ is inhuman? We all go through ups and downs, we all battle our demons, one way or another, at some point or another. That the fight is more or less intense and lengthy doesn’t matter, we all go through it. So yes, I believe that this is normal, that it is human. We are all ‘normal’, including everyone with disorders and illnesses, mental or physical. You don’t say to someone with cancer that he is not normal. You say they have an illness. The same goes for someone depressed, bulimic, with a compulsive disorder etc. You should say they have an illness. And what you do in both cases, physical and mental predicaments, is to give your support while they fight it.

In fact, I am grateful that I was not always balanced. It enables me to understand and empathise better with people who are in a dark place, who are unstable, or who are struggling inside and need support. Could it be that the experience made me more human? If so, could it mean that being always ‘normal’ is inhuman? We all go through ups and downs, we all battle our demons, one way or another, at some point or another. That the fight is more or less intense and lengthy doesn’t matter, we all go through it. So yes, I believe that this is normal, that it is human. We are all ‘normal’, including everyone with disorders and illnesses, mental or physical. You don’t say to someone with cancer that he is not normal. You say they have an illness. The same goes for someone depressed, bulimic, with a compulsive disorder etc. You should say they have an illness. And what you do in both cases, physical and mental predicaments, is to give your support while they fight it.

True, one key syndrome of most acute mental disorders is the lack of empathy, and that is difficult to understand, accept or live with when you have aplenty. In some cases, it makes the individual dangerous and the society must protect itself from the danger he represents. However, in most others, the individual may sim ply have another way of seeing the world. You don’t have to agree with it, just be tolerant of someone’s different way of thinking. Literature helped understand this, with books like The Girl With The Dragon’s Tattoo in which the heroine has Asperger’s Syndrome.

ply have another way of seeing the world. You don’t have to agree with it, just be tolerant of someone’s different way of thinking. Literature helped understand this, with books like The Girl With The Dragon’s Tattoo in which the heroine has Asperger’s Syndrome.

What matters is not whether or not there is a normality and what it is supposed to be. What matters is our humanity, and how to make it come first. We all have limits of what we do and can accept from others, but let’s give our best shot to understand and be supportive.

Thank you for reading.

Yours, Virginie